I like rain. Being British, this is a useful trait. It’s also what led me to do a PhD in Hydrometeorology. Since then, I have researched in hydrology, hydraulics, geomorphology, and more recently I have dabbled in sedimentology. Yet, the common theme through all of my research has been rain.

I think it’s often underappreciated by those of us more interested in dry stuff like sediment and rocks, but speak to any hydrometeorologist or hydrologist and they will be able to tell you at length just how troublesome the wet stuff is. For starters there is no accurate way to even tell how much is falling over an area, and this has led to some creative methods of measuring it, mainly from EGU stalwart, Rolf Hut.

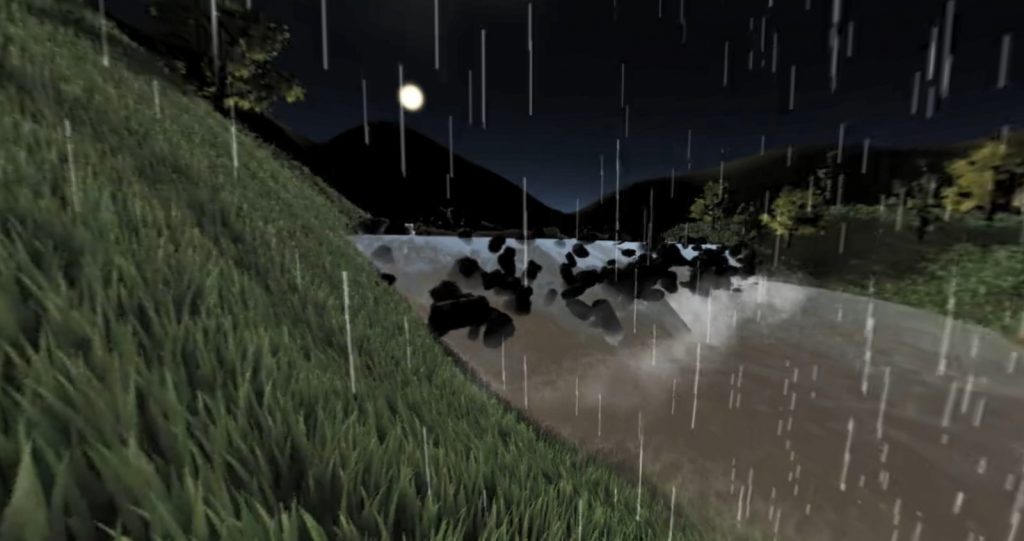

Rain is a big theme in my SeriousGeoGames

Another issue is that it doesn’t just come in one type and each can have a different impact on sediments. Frontal rain is miserable and can bring day after day of rain, adding a lot of water to the land but spread out over a long time this is often not enough to have an impact the land surface. Convective rainfall can be extremely heavy, extremely localised, and can have huge impacts on the land – just look at the recent flooding in Coverack, UK.

This complicates things – we like to lump rainfall together and climatically we think about mean annual totals. However, by shifting the balance from low- to medium-intensity frontal rain to high-intensity convective rain it is possible that with no change in the mean annual totals there will be an increase in geomorphic activity. It is even possible that the mean annual rainfall total could decrease, but if summer convective storms increase in frequency and magnitude, the sediment yields of catchments will increase.

To try and simplify this, the variability of rainfall often has a greater impact on sediment processes than the amount of rainfall. This can also influence the shapes of landscapes and how they develop – in my work with Professor Tom Coulthard we showed how using the same rainfall totals at different spatial and temporal resolutions impacted the sediment yields predicted by the CAESAR-Lisflood model. We found that when using the finest resolution, the sediment yields could be more than double those using a daily total and spatial homogenous rainfall rates – this could be taken as analogous of the same rainfall totals applied as convective and frontal. Over 1000 years of simulation the convective higher-resolution data produced more erosion higher up in the catchment, and increase deposition in the valley floors.

The CatchyRain Team setting up their next experiment

I wanted to follow this up by seeing if we could get similar results using a sediment flume. However, I’ve been beaten to it by the CatchyRain group from Wageningen University who have been conducted experiments via the Hydralab+ programme. Fortunately, they conducted their experiments using the Total Environment Simulator at my University, Hull, and they kindly let me visit and film some of it on my 360 camera – in the video below I speak to Dr Jantiene Baartman, Assistant Professor from Wageningen University. You will also see others involved in the test, such as Dr Martine van der Ploeg, and Hull’s Dr Hannah Williams and Dr Wietse van de Lageweg. To get the best effect out of this video, view it on a mobile device via the YouTube app.

What the Wageningen and Hydralab+ team will hopefully show is that even the same volume of rainfall falling on a catchment will produce different patterns of sediment processes due to the variability in intensities. I am really looking forward to seeing the results presented at EGU 2018, for example this Highlight presentation by Hannah.

This is just the tip of the iceberg in terms of how complicated rainfall is and how its variations and variability can influence landscapes. I haven’t had chance to open the Pandora’s Box of how the uncertainty in rainfall estimations can cascade through modelling processes – maybe another blog for another time. In the meantime, I hope I will have inspired you to think about rain a little more and for EGU 2018 I would highly recommend a visit to the HEPEX sessions.