Media highlights

You are viewing the EGU General Assembly 2021 Press Centre page. Click here to see information about media services and activities (e.g. press conferences) at the most recent General Assembly.

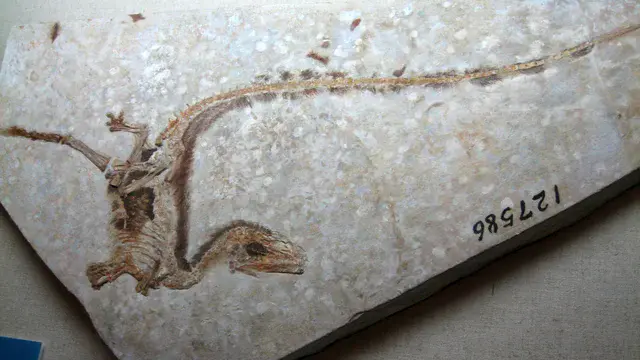

The evolution of feathers

Birds are covered in feathers, but they are not the only animal to sport a colorful coat. Dinosaurs once did too, according to recent scientific findings. Researchers have uncovered fossils that show feathers existed 100 million years ago and were likely on all dinosaur groups.

Michael Benton, paleontologist at the University of Bristol, UK, presents research on Tuesday, 20 April at 15:05 CEST covering the evolution of feathers, including how paleontologists are detecting colours and patterns of dinosaur feathers. He will also discuss new frontiers of research in paleobiology.

Lessons learned when an earthquake struck during the pandemic

The deadliest earthquake of 2020 occurred amid the global COVID-19 pandemic. When a magnitude-6.9 quake struck the eastern Aegean Sea in October, 119 people died in Turkey and Greece, predominantly from buildings collapsing. It was the scene emergency responders and natural hazards scientists had feared: a major quake occurring during the pandemic.

Normal actions immediately following an earthquake — like search and rescue, first-aid treatment, and setting up emergency shelters — were riskier and more challenging because of COVID. For example, responders needed proper personal protective equipment, especially facemasks, and the affected population also needed masks.

Learn more about the emergency response in a presentation by Spyridon Mavroulis, of the National and Kapodistrian University of Athens in Greece, on Monday, 26 April at 11:20 CEST. This session includes additional presentations on COVID and earthquakes.

Social media and machine learning help humanitarian relief efforts

Humanitarian relief efforts, such as those offered by the Red Cross or World Food Programme, need access to up-to-date information about incidents and disasters. Could social media be another tool in the fast-paced humanitarian relief toolbox?

That’s what a team from Germany hoped to find out during their project Data4Human. The team combined webdata, using everything from satellite imagery to Twitter to data from the real-time global event database, with machine learning to offer new on-demand data services for humanitarian aid. Twitter and other citizen-science-related social media offer on-the-ground information that satellites and other remote sensing cannot, while remote sensing can show the big picture that social media accounts might miss. The team tested the new approach during two cyclones in 2019.

Their results will be presented by Jens Kersten of the German Aerospace Center on Monday, 26 April at 13:47 CEST.

Seismometers reveal where and how underground water flows

Karst landscapes underlie approximately one-quarter of all land on Earth. And aquifers in those karst landscapes provide water to hundreds of millions of people worldwide. Many cities, including Vienna and Rome, depend predominantly on karst aquifers for this precious resource, so knowing how an aquifer functions can be quite important.

To image an aquifer in the Jura Mountains, a team from France combined seismological, hydrological, and atmospheric data. The results indicate that seismometers can reveal a clear picture of what’s going on inside karstic reservoirs when rain falls at the surface.

Their results, based on detecting fluid saturation changes in the rocks, will be presented by Anthony Abi Nader of the Université Bourgogne Franche-Comté, in France, on Tuesday, 27 April at 09:24 CEST.

The weight of it all: how Antarctic glaciers trigger icequakes

Scientists have only known for a few decades that the weight of glaciers can cause earthquakes—often called “icequakes”. Now, researchers are looking at how climate-induced changes in ice might affect its seismic activity.

Since 2015, seismic stations around Perunica Glacier, on Livingston Island, Antarctica have been recording activity. More than 16,000 icequakes were measured, with the duration lasting from less than a second up to more than a minute.

Scientists looked at the Perunica data and parsed out the source and drivers of each icequake.

Intriguingly, they found that between 2015 and 2020 the number of glacial events increased, while the average duration of shaking during each icequake decreased. To better understand why, the team is now investigating the location and type of events within the Perunica glacier.

Gergana Georgieva, associate professor at Sofia University, Bulgaria will present results from their work on Tuesday, 27 April at 9:46 CEST.

Feeling the rhythm—a new way to hear about coastal geoscience

How can scientists better communicate the power, danger, and environmental impacts of the ocean? A musician-geoscientist pair have teamed up to present the dynamic nature of rocky coastlines in a new way: with sound.

“Drumming the Waves” is a U.S. National Science Foundation-funded programme that uses sound to showcase the chaos, rogue waves, and ocean swells that can affect coastal areas. Using a combination of natural sounds and studio processing, the team created a cacophony that can be “unpredictable, sometimes chaotic, and occasionally extreme.” Like the ocean itself.

Cormac Byrne, researcher at the University of Limerick, will present details about the project and how it can be used to better communicate coastal science to students and the general public on Wednesday, 28 April at 9:17 CEST.

Jordanian pottery reveals magnetic field strength

Earth’s magnetic field, which protects us from solar radiation, shifts up to 10 degrees a year and strengthens and weakens over time. And every so often, it flips entirely, so what was north becomes south, and vice versa. Due to the magnetic field’s changes over time, measurements of these magnetic variations are powerful tools for dating archaeological sites.

Now, flint, along with ancient pottery, has been used to measure the strength of the magnetic field about 9,600 years ago. A team of researchers measured the strength of Earth’s magnetic field in both materials from prehistoric sites in Jordan at three different periods: 7600, 7100, and 5200 BCE. The results reveal that the magnetic field was weak in the Southern Levant in 7600 BCE, stronger in 7100 BCE, and then weaker again in 5200 BCE.

In addition, the results suggest that flint, which is found at human sites from prehistoric periods before the invention of pottery, has the potential to extend the archaeomagnetic record. Anita Di Chiara of INGV in Italy and Scripps Institution of Oceanography at the University of California, San Diego, will present the findings on Wednesday, 28 April at 13:44 CEST.

A strategy for achieving net-zero emissions by 2050

Balancing all greenhouse gas emissions with carbon storage and capture solutions will take an integrated approach. Economist Sir David Hendry of the University of Oxford and his colleague Jennifer Castle have proposed using a combined strategy, including better energy storage with graphene-based nanotubes (GNTs), using hydrogen fuels during “off-peak” times, retrofitting houses for energy use, taxing high-carbon products, and changing farming practices, including meat production and agricultural crops.

Hendry presents an analysis of their emission-reduction strategies on Wednesday, 28 April at 13:59 CEST from both an economic and a climatic perspective.

Extreme cyclones in the Arctic and their effects on weather around the world

As the world’s climate changes, the Arctic is experiencing rapid and amplified warming. These increasing temperatures influence weather patterns, impacting droughts, floods, coastal erosion, and wildfires around the world, and have the potential to further amplify Arctic warming.

Researchers are diving into one of the most extreme Arctic weather events—cyclones—to better understand how they form and what effects they have on the atmosphere. Because these cyclones often occur in the winter and are triggered by heat and moisture transport into the Arctic, they have the potential to slow sea-ice growth in the fall or initiate melting earlier in the spring.

To get a better understanding of the patterns and underlying mechanisms of Arctic cyclones, a team led by Dörthe Handorf, senior scientist at Alfred Wegener Institute Helmholtz Centre for Polar and Marine Research in Potsdam, Germany, looked into the connections of atmosphere, sea surface temperatures, and sea-level pressures and cyclone events between 1979-2019. Handorf will present their findings on Thursday, 29 April at 11:02 CEST.

Satellite data help save water and limit emissions from rice paddies

Rice is the second-most important cereal grain in the world. But it also is the most greenhouse-gas intensive, accounting for 11% of global anthropogenic methane releases. One way to reduce methane emissions — and simultaneously mitigate drought risk, thereby helping with food security — is to implement water-saving irrigation practices like “alternate wetting and drying.” To execute this most effectively, it’s important to know how wet soils in the paddies already are. One team says using satellite data is the best way to tell this.

Hironori Arai of Université Paul Sabatie, France and the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science, and a team from Japan will present their research in the Vietnamese Mekong Delta on Thursday, 29 April at 13:52 CEST. From 2012 to 2017, the team used satellites to look at alternate wetting and drying practices in rice paddies, especially soil inundation. Using this information, the team then developed a model that incorporates multi-sensor data to reveal rice productivity and greenhouse gas emissions from the paddies.

Given that 90% of rice paddy-production comes from Asia, and there’s little more land or water to develop despite growing needs for more food production, it’s important to learn to manage rice production sustainably, the team notes.

Olive orchard sequesters carbon — if managed right

Apparently, weeds can be good for something: aiding carbon sequestration in an olive orchard. A 20-year experiment in an Italian orchard shows that managing olive groves sustainably — including letting weeds grow in between trees — can have significant benefits, from healthier soils to carbon sequestration. Given the prevalence of olive agriculture in the Mediterranean region, switching to more sustainable methods could make a big difference in the region’s carbon budget, researchers say.

In the long experiment, sustainable olive production included everything from drip irrigation using urban wastewater to spreading cover crop residues and prunings as mulch. Weeds were even allowed to grow in between the trees. The half of the orchard managed with conventional methods, including weed control and removing prunings from the orchard — the control group — sequestered far less carbon than the half of the orchard that was sustainably managed.

Their results — including that carbon was locked up in both soils and plants (weeds!) in the sustainably managed orchard at far higher rates than in the conventional olive orchard — will be presented by Adriano Sofo of the University of Basilicata – Potenza/Matera, Italy on Thursday, 29 April at 14:38 CEST.

Etna’s lava fountains cause gravity changes

As magma accumulates in a reservoir below the surface of a volcano, gravity usually increases, and then decreases once the volcano erupts. So gravity increases can sometimes be a warning sign of an impending eruption. At Mount Etna on the Italian island of Sicily, gravity measurements taken before explosive lava fountains erupted in 2011 showed a pre-eruption decrease in gravity. Researchers now suggest it may be because of the shape of the magma chamber and how it interacts with gases.

Mount Etna is one of the world’s most active volcanoes. In February 2021, Etna started putting on its latest show, intermittently shooting explosive lava fountains up to 1.5 kilometers high.

On Friday, 30 April at 11:20 CEST, Luigi Passarelli of the University of Geneva in Switzerland and his colleagues will present their model results, which simulate a time series of gravity changes at Etna. The final goal, the team notes, is to use their gravity simulations to develop a model to predict the amount of magma and duration of lava fountains at Etna.

Movement on submarine faults can contribute to tsunami risk in North Iceland

Tsunamis are generally caused by earthquakes on submarine faults where movement is primarily vertical. This is especially the case for movement on megathrust faults along plate boundaries. While strike-slip faults, which accommodate mostly horizontal motion, don’t usually disturb the water column, they can combine with vertical fault movement to produce big disruptions. The 2018 Mw 7.5 Sulawesi, Indonesia earthquake had both horizontal and vertical movement, which together created a devastating tsunami. This event has led scientists to re-think movement on other faults that have some strike-slip motion.

In North Iceland, researchers reassessed the ~100-kilometer-long Húsavík Flatey fault (HFF), which has both strike-slip and dip slip (normal) motion, to see if there was the potential for a devastating tsunami.

A team of researchers led by Fabian Kutschere, of Ludwig Maximilians University in Munich, Germany, will present the latest results of their modeling of the HFF with earthquakes similar in size to historical M>6 events, and show the potential for tsunamis to overwhelm the northern coast and town of Húsavík. The presentation is on Friday, 30 April at 15:45 CEST.