Media highlights

You are viewing the EGU General Assembly 2022 Press Centre page. Click here to see information about media services and activities (e.g. press conferences) at the most recent General Assembly.

Robots might make mining safer, sustainable

Robots could help make future mining safer and more sustainable, especially as the world pivots to green technologies that require more raw materials. The ROBOMINERS consortium aims to decrease or eliminate the presence of people at certain mines, produce less mining waste and require less infrastructure by merging robotics with geoscientific knowledge. In particular, the consortium’s robot-miner will help the EU obtain raw materials domestically from otherwise inaccessible or uneconomic sources.

During the last two years, the consortium has focused on components and capabilities. They plan to have their first robotic prototype in December 2022. Trials at test mines in the EU are tentatively scheduled for 2023.

Luís Lopes, a geoscientist at the La Palma Research Centre in the Canary Islands, Spain, presents this research on Monday, 23 May at 11:20 CEST, providing an update on the robot-miner concept, as well as the ecosystem in which such a robot would function — from computer models to transportation of mining materials.

Can we quantify an individual’s impact on extreme weather?

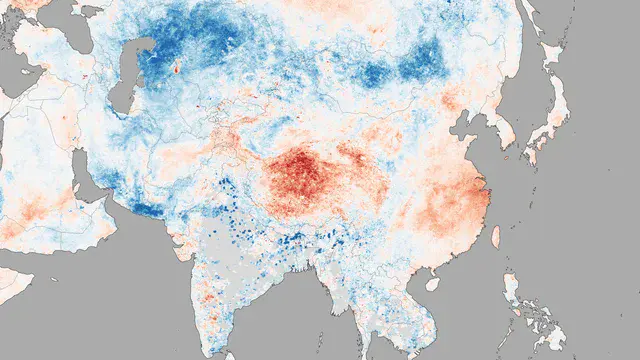

Scientists and governments alike grapple with the question of whether certain nations or older generations have greater responsibility for the burdens of climate change — like the 2018 Chinese heatwave — and if a cost can be ascribed to such events that stem from a warming world.

Fraser Lott, a physicist at the Met Office Hadley Center, United Kingdom, presents how scientists are using the Chinese heatwave as a test case to examine how a portion of the economic cost of such a climate-driven catastrophe can be subdivided at the level of individuals. Such a quantitative method provides an approach not only for individuals to understand their impact on climate, but also can provide governments the necessary information to distribute the costs that climate change will certainly present. Lott presents the team’s findings on Monday, 23 May at 16:14 CEST.

African environment and early humans evolved together

As water availability changes, so should the dispersal patterns of plants and animals. By combining records from land and sea spanning the last 620,000 years, scientists are sorting out just how climate variations modified moisture patterns in Africa when early modern humans were evolving.

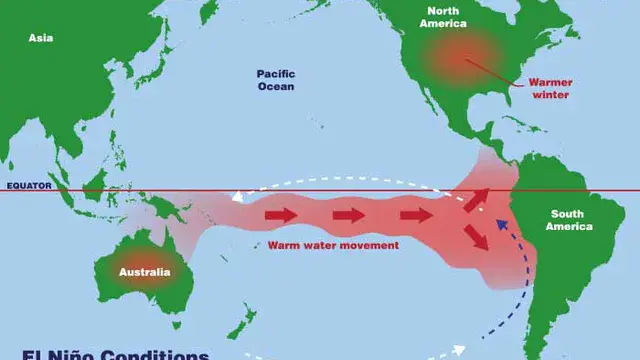

Stefanie Kaboth-Bahr, a paleoclimate scientist at the University of Potsdam, Germany, discusses a tight correlation between the El Niño-Southern Oscillation and moisture availability across Africa, possibly driven by changes in Earth’s eccentricity — how much Earth’s orbit around the sun departs from a circle.

These processes — especially related to precipitation and temperature resulting from the El Niño-Southern Oscillation — may have affected not only the evolution of vegetation and many mammals, but also early hominins. This presentation is on Tuesday, 24 May at 9:25 CEST.

Mines move backward via erosion during floods

On 15 July 2021, intense rains caused extreme floods to tear across western Germany. Two surficial mining areas in the North-Rhine Westphalia area — one coal and the other gravel, both open pits — reacted to the floods by eroding backward.

In the case of the coal mine, parts of an old river channel — artificially abandoned to accommodate mining — were reoccupied by the floods. Rapid erosion and of the old channel, along with backward erosion, created a gorge 540 meters long and five meters deep, with a total of 500,000 cubic meters of sediment eroded and moved into the mining area.The gravel mine tells a similar story, except that backward erosion reached the settlement of Blessem, destroying or damaging several houses.

Frank Lehmkuhl of Aachen University, Germany, presents this research and other findings about the geomorphologic processes that occur when mines meet floods on Tuesday, 24 May at 9:38 CEST.

Historic spy images site Earth’s poles

Understanding what glaciers were doing at Earth’s poles before satellites regularly streaked across the sky can be difficult because such data are sparse. Using declassified imagery from historic satellite archives — like Soviet Era KFA-1000 satellite imagery — can help.

Flora Huiban, a geographer at the University of Copenhagen, Denmark, presents research on Tuesday, 24 May at 17:31 CEST about how Soviet and American satellite data can be combined with other aerial imagery. These rich datasets can provide detailed pictures of how volumes of Antarctica and Greenland ice evolved. The records Huiban is using will be made freely available.

Car crowdsensing helps scientists find urban heat islands

As cities grow, they’ll certainly get hotter simply from the urban heat island effect that results from the replacement of natural land cover with heat-retaining concrete and buildings. This increased heat can become a serious health concern by causing people to overheat more easily. If city planners could access meteorological data indicating the location of urban heat islands, they could better attend to those who need it most.

Eva Marques, a climatologist at Centre National de Recherches Météorologique, France, explores collecting temperature measurements via thermometers embedded in people’s private cars on Wednesday, 25 May at 8:47 CEST. Marques found that by aggregating private car temperature measurements, they could estimate urban heat island locations at a resolution of 200 meters. Such data could be used to create maps for urban planners, helping them target areas most prone to such effects.

Wildfires burn so hot they heat up the atmosphere

Higher global temperatures are leading to more frequent and more severe wildfires around the world. But new research shows that wildfires are also causing the atmosphere to warm as well, in a vicious feedback cycle.

Matthias Stocker of the University of Graz in Austria and his colleagues examined satellite data from the extreme 2017 North American fire season and the 2019/2020 fire season in Australia. They found “strong effects” of the fires on temperatures in the upper atmosphere, called the stratosphere. Fires heated the lower stratosphere — 10 kilometers above Earth’s surface or higher — 10 degrees Celsius immediately, and the warm effects lasted months. The North American fires caused a 1-degree-Celsius increase that lasted months after the fires were extinguished, and the Australian fires increased temperatures by 3.5 degrees Celsius! Considering fires are generally thought to cool Earth by blocking out the sun’s rays, much the way volcanic ash cools the planet, these are startling findings.

Stocker presents the team’s findings and analysis Wednesday, 25 May, at 15:26 CEST. Head to the session earlier that day to learn more about fire’s effects on planetary systems.

Finding new sources of rare earth elements from waste

Rare earth elements are essential to modern society. They are used in everything from smartphones and computers to electric cars. But their name divulges the challenge of these vital elements: they’re rare. Now, a team of Danish researchers has found that waste, like coal fly ash and mine tailings, could potentially be converted into a resource for rare earth elements.

Coal fly ash and stormwater retention ponds are two of the most promising sources of rare earth elements, the team reports. Stormwater retention ponds, which are common in urban areas, present the highest amount of usable rare earth elements among the waste sources tested. Recycling and finding renewable sources of rare earth elements is important for achieving a circular, carbon-neutral economy, the team reports. Find out more in a session on resource recovery on Thursday, 26 May at 11:09 CEST. Ana Teresa Lima of the Technical University of Denmark presents this research.

Historical and cultural sites at risk from sea-level rise

Some UNESCO World Heritage Sites, like Venice, Italy, and the ruins of Carthage in Tunisia, are already experiencing damage from rising seas. The Phoenician naval base of Carthage is already underwater. By 2100, dozens more will join them. According to a new analysis, rising seas may inundate 136 individual UNESCO cultural and historical treasures around the world.

Current on-land cultural heritage sites may soon have to join the remains of an underwater Byzantine port in Istanbul and a Viking trading port in Hedeby, Germany, among many other sites to become part of UNESCO’s “underwater cultural heritage,” she notes.

At a presentation on Thursday, 26 May, at 15:45 CEST, Elena Pérez Álvaro of Nelson Mandela University in South Africa explores how many sites may be endangered from rising seas, how submergence will affect the sites themselves, and what might be done to preserve these important sites.

The rest of the session brings other presentations on how climate change is affecting cultural heritage around the world.

Astronauts need emotional intelligence

Long-duration space travel — one of the most demanding environments in which people can work — requires more than just physical fitness. Emotions involve both physiological and mental processes, and managing emotions in such environments is paramount to the success of the task at hand. By giving questionnaires to analog astronauts in Europe, psychologists can begin to explore whether training in emotional intelligence can affect cognitive processes. Maintaining mental agility is of upmost importance to future long-term astronauts who must minimize their fatigue and stress while maintaining their attention and vigilance.

Psychologist Celia Avila-Rauch presents findings on Thursday, 26 May at 15:57 CEST.

Uganda citizen science initiative interviews elders

Uganda’s mountainous Kigezi highlands alternate between intensely rainy wet seasons and parching dry spells. Combined with its high population density, natural hazards like landslides, floods, storms and earthquakes are all concerns denizens of the region. Deforestation has further exacerbated the unpredictability of such hazards.

To better understand the landscape characteristics and dynamics that control the myriad natural hazards, researchers conducted a three-part study. Fifteen citizen scientists were trained to use smartphones to collect information about processes and impacts about eight different natural hazards occurring in their communities. An additional eight river watchers monitored stream flow characteristics to increase data relevant to flash floods, a particular scourge. Ninety-six elderly citizens, each more than 70 years of age, were interviewed to reconstruct landscape changes and natural hazard occurrence through time.

Violet Kanyiginya, a natural hazards researcher at the Royal Museum for Central Africa in Belgium, discusses the results of this multifaceted project on Friday, 27 May at 8:35 CEST, including a reconstructed timeline of hazards in the region and ongoing data collection efforts.

Archaeology helps scientists sort out climate and volcanism impacts

When volcanoes erupt, the climate can change, especially at timescales of years to decades. Understanding climate variability of the recent past — and any concomitant volcanic eruptions — can help scientists better understand how the interaction between the two affects people.

One way to address this problem involves archaeological data. Frank Arthur, a meteorologist at the University of South-Eastern Norway, presents research on Friday, 27 May at 8:38 CEST exploring how large volcanic eruptions in 536 AC and 540 AD may have contributed to a cooling climate, causing troubles for societies throughout Europe. In particular, Arthur compared archaeological records from Scandinavia demarcating land use with results from a computer model that varied the level of climate change caused by volcanic eruptions. He discusses his findings about the impacts of volcanic activity on 6th-century Scandinavians.

Industry threatens Indigenous reindeer caretakers in Sweden

In Sweden, an Indigenous group — the Sámi — practice reindeer husbandry across Norway, Sweden and Finland. Sweden’s forests are experiencing an influx of industry, including large-scale clear-cutting for timber and wind power plants. Such industries can threaten the livelihood of the Sámi, as well as the reindeer themselves.

Elaine Mumford, a social scientist at Uppsala University, Sweden, presents research on Friday, 27 May at 9:45 CEST, in which they argue that the Sámi way of life is under threat because of a combination of anti-Sámi racism and a sense of entitlement to these resources. The presentation explores a case study focused on the Gällivare Forest Sámi Community that looks at these encroachments and impacts not as a set of disparate problems, but rather as a coupled system.