The Coldest Decade of the Millennium? How the cold 1430s led to famine and disease

While searching through historical archives to find out more about the 15th-century climate of what is now Belgium, northern France, Luxembourg, and the Netherlands, Chantal Camenisch noticed something odd. “I realised that there was something extraordinary going on regarding the climate during the 1430s,” says the historian from the University of Bern in Switzerland.

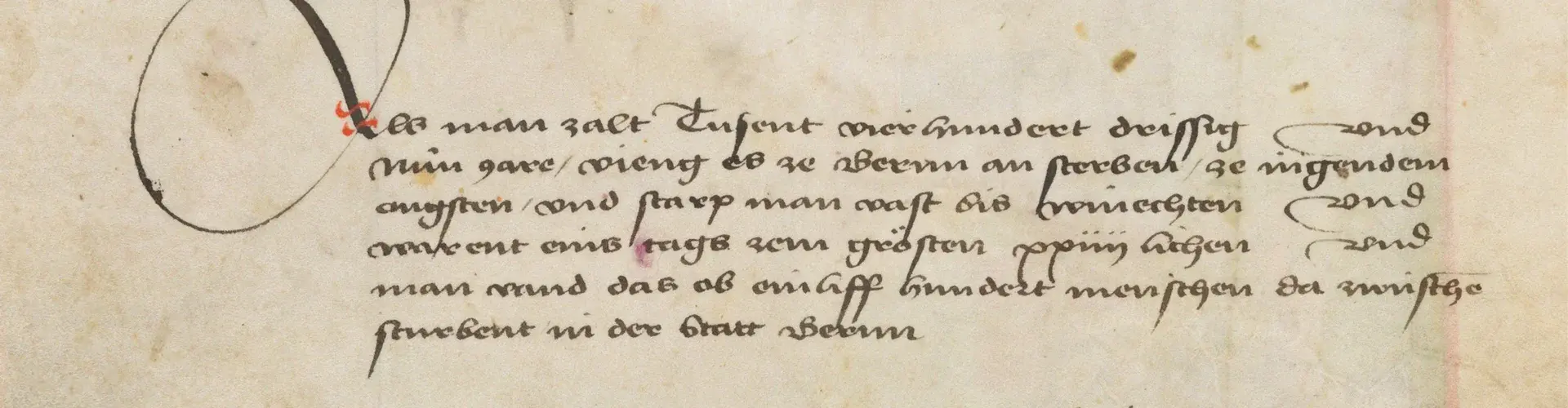

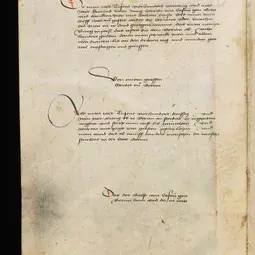

Compared with other decades of the last millennium, many of the 1430s’ winters and some springs were extremely cold in the Low Countries, as well as in other parts of Europe. In the winter of 1432–33, people in Scotland had to use fire to melt wine in bottles before drinking it. In central Europe, many rivers and lakes froze over. In the usually mild regions of southern France, northern and central Italy, some winters lasted until April, often with late frosts. This affected food production and food prices in many parts of Europe. “For the people, it meant that they were suffering from hunger, they were sick and many of them died,” says Camenisch.

She joined forces with Kathrin Keller, a climate modeller at the Oeschger Centre for Climate Change Research in Bern, and other researchers, to find out more about the 1430s climate and how it impacted societies in northwestern and central Europe. Their results are published today in Climate of the Past, a journal of the European Geosciences Union.

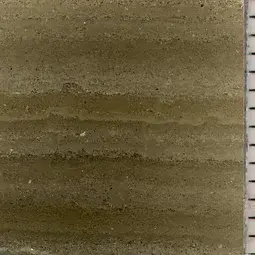

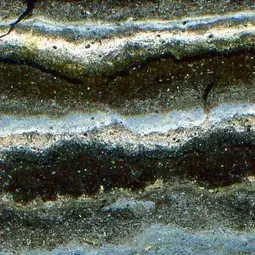

They looked into climate archives, data such as tree rings, ice cores, lake sediments and historical documents, to reconstruct the climate of the time. “The reconstructions show that the climatic conditions during the 1430s were very special. With its very cold winters and normal to warm summers, this decade is a one of a kind in the 400 years of data we were investigating, from 1300 to 1700 CE,” says Keller. “What cannot be answered by the reconstructions alone, however, is its origin – was the anomalous climate forced by external influences, such as volcanism or changes in solar activity, or was it simply the random result of natural variability inherent to the climate system?”

There have been other cold periods in Europe’s history. In 1815, Mount Tambora – a volcano in Indonesia – spewed large quantities of ash and particles into the atmosphere, blocking enough sunlight to significantly reduce temperatures in Europe and other parts of the world. But the 1430s were different, not only in what caused the cooling but also because they hadn’t been studied in detail until now.

The climate simulations ran by Keller and her team showed that, while there were some volcanic eruptions and changes in solar activity around that time, these could not explain the climate pattern of the 1430s. The climate models showed instead that these conditions were due to natural variations in the climate system, a combination of natural factors that occurred by chance and meant Europe had very cold winters and normal to warm summers. [See note]

Regardless of the underlying causes of the odd climate, the 1430s were “a cruel period” for those who lived through those years, says Camenisch. “Due to this cluster of extremely cold winters with low temperatures lasting until April and May, the growing grain was damaged, as well as the vineyards and other agricultural production. Therefore, there were considerable harvest failures in many places in northwestern and central Europe. These harvest failures led to rising food prices and consequently subsistence crisis and famine. Furthermore, epidemic diseases raged in many places. Famine and epidemics led to an increase of the mortality rate.” In the paper, the authors also mention other impacts: “In the context of the crisis, minorities were blamed for harsh climatic conditions, rising food prices, famine and plague.” However, in some cities, such as Basel, Strasbourg, Cologne or London, societies adapted more constructively to the crisis by building communal granaries that made them more resilient to future food shortages.

Keller says another decade of very cold winters could happen again. “However, such temperature variations have to be seen in the context of the state of the climate system. Compared to the 15th century we live in a distinctly warmer world. As a consequence, we are affected by climate extremes in a different way – cold extremes are less cold, hot extremes are even hotter.”

The team says their Climate of the Past study could help people today by showing how societies can be affected by extreme climate conditions, and how they should take precautions to make themselves less vulnerable to them. In the 1430s, people had not been exposed to such extreme conditions before and were unprepared to deal with the consequences.

“Our example of a climate-induced challenge to society shows the need to prepare for extreme climate conditions that might be coming sooner or later,” says Camenisch. “It also shows that, to avoid similar or even larger crises to that of the 1430s, societies today need to take measures to avoid dangerous anthropogenic climate interference.”

###

Please mention the name of the publication (Climate of the Past) if reporting on this story and, if reporting online, include a link to the paper (http://www.clim-past.net/12/2107/2016) or to the journal website (http://www.climate-of-the-past.net).

Note

Even without the influence of external factors, the climate can vary naturally because of the way the different components of the climate system (such as atmosphere, oceans or land) interact with each other. El Niño, a warming of the eastern equatorial Pacific Ocean, is an example of natural variability. This phenomenon happens every 2 to 7 years and causes changes in temperature and rainfall also in other parts of the world for months. The type of natural variability responsible for the 1430s climate conditions is another, much less common, example.

More information

This research is presented in the paper ‘The 1430s: A cold period of extraordinary internal climate variability during the early Spörer Minimum with social and economic impacts in Northwestern and Central Europe’, published in the EGU open access journal Climate of the Past on 1 December 2016.

The paper summarises the results from the workshop ‘The Coldest Decade of the Millennium? The Spörer Minimum, the Climate during the 1430s, and its Economic, Social, and Cultural Impact’, held at Oeschger Centre for Climate Change Research in Bern in December 2014.

Citation: Camenisch, C., Keller, K. M., Salvisberg, M., Amann, B., Bauch, M., Blumer, S., Brázdil, R., Brönnimann, S., Büntgen, U., Campbell, B. M. S., Fernández-Donado, L., Fleitmann, D., Glaser, R., González-Rouco, F., Grosjean, M., Hoffmann, R. C., Huhtamaa, H., Joos, F., Kiss, A., Kotyza, O., Lehner, F., Luterbacher, J., Maughan, N., Neukom, R., Novy, T., Pribyl, K., Raible, C. C., Riemann, D., Schuh, M., Slavin, P., Werner, J. P., and Wetter, O.: The 1430s: a cold period of extraordinary internal climate variability during the early Spörer Minimum with social and economic impacts in north-western and central Europe, Clim. Past, 12, 2107-2126, doi:10.5194/cp-12-2107-2016, 2016.

The team is composed of Chantal Camenisch (Oeschger Centre for Climate Change Research [OCCR] and Institute of History [Hist], University of Bern), Kathrin M. Keller (OCCR and Physics Institute [Phys] University of Bern), Melanie Salvisberg (OCCR and Hist), Benjamin Amann (OCCR; Institute of Geography [Geo], University of Bern; Queen’s University, Kingston, Canada), Martin Bauch (German Historical Institute in Rome), Sandro Blumer (OCCR and Phys), Rudolf Brázdil (Geo and Czech Academy of Science), Stefan Brönnimann (OCCR and Geo), Ulf Büntgen (OCCR; Czech Academy of Sciences; Swiss Federal Research Institute WSL), Bruce M. S. Campbell (The Queen’s University of Belfast), Laura Fernández-Donado (Institute of Geosciences, University Complutense, Madrid [UCM-CSIC]), Dominik Fleitmann (University of Reading), Rüdiger Glaser (University of Freiburg), Fidel González-Rouco (UCM-CSIC), Martin Grosjean (OCCR and Geo), Richard C. Hoffmann (York University, Toronto, Canada), Heli Huhtamaa (OCCR; Hist; University of Eastern Finland), Fortunat Joos (OCCR and Phys), Andrea Kiss (Vienna University of Technology), Oldrich Kotyza (Regional Museum, Litoměřice, Czech Republic), Flavio Lehner (National Center for Atmospheric Research, Boulder, USA), Jürg Luterbacher (Justus Liebig University of Giessen), Nicolas Maughan (Aix-Marseille University), Raphael Neukom (OCCR and Geo), Theresa Novy (Johannes Gutenberg University of Mainz), Kathleen Pribyl (University of East Anglia), Christoph C. Raible (OCCR and Phys), Dirk Riemann (University of Freiburg), Maximilian Schuh (University of Heidelberg), Philip Slavin (University of Kent), Johannes P. Werner (University of Bergen), Oliver Wetter (OCCR and Hist).

The European Geosciences Union (EGU) is Europe’s premier geosciences union, dedicated to the pursuit of excellence in the Earth, planetary, and space sciences for the benefit of humanity, worldwide. It is a non-profit interdisciplinary learned association of scientists founded in 2002. The EGU has a current portfolio of 17 diverse scientific journals, which use an innovative open access format, and organises a number of topical meetings, and education and outreach activities. Its annual General Assembly is the largest and most prominent European geosciences event, attracting over 11,000 scientists from all over the world. The meeting’s sessions cover a wide range of topics, including volcanology, planetary exploration, the Earth’s internal structure and atmosphere, climate, energy, and resources. The EGU 2017 General Assembly is taking place in Vienna, Austria, from 23 to 28 April 2017. For information about meeting and press registration, please check http://media.egu.eu, or follow the EGU on Twitter and Facebook.

If you wish to receive our press releases via email, please use the Press Release Subscription Form at http://www.egu.eu/news/subscribe/. Subscribed journalists and other members of the media receive EGU press releases under embargo (if applicable) at least 24 hours in advance of public dissemination.

Climate of the Past (CP) is an international scientific journal dedicated to the publication and discussion of research articles, short communications, and review papers on the climate history of the Earth. CP covers all temporal scales of climate change and variability, from geological time through to multidecadal studies of the last century. Studies focusing mainly on present and future climate are not within scope.

Contact

Chantal Camenisch

Researcher at the Oeschger Centre for Climate Change Research and the Institute of History

University of Bern

Bern, Switzerland

Phone +41 31 631 50 99

Email chantal.camenisch@hist.unibe.ch

Kathrin M. Keller

Postdoc

Climate and Environmental Physics & Oeschger Centre for Climate Change Research

University of Bern

Bern, Switzerland

Phone +41 31 631 4871

Email keller@climate.unibe.ch

Bárbara Ferreira (if unavailable, please contact Laura Roberts)

EGU Media and Communications Manager

Munich, Germany

Phone +49-89-2180-6703

Email media@egu.eu

EGU on Twitter: @EuroGeosciences

Laura Roberts

Communications Officer

Munich, Germany

Phone +49-89-2180-6717

Email networking@egu.eu

EGU on Twitter: @EuroGeosciences

Kaspar Meuli

Communications Coordinator

Oeschger Centre for Climate Change Research

Phone +41 31 631 31 49

Email kaspar.meuli@oeschger.unibe.ch

Links

- Scientific paper

- Journal – Climate of the Past

- Oeschger Centre for Climate Change Research, University of Bern

- Read this press release in simplified language, aimed at 7–13 year olds, on our Planet Press site